As promised, NGS instruments are yielding thousands of new genome sequences. Read lengths and throughputs are increasing. Alignment and analysis algorithms are getting more mature. Databases of sequence variants are growing exponentially. Things are looking pretty good, right? Sure, there are lots of variants still waiting to be discovered. Sure, some of those already reported simply aren’t real. But I think we’re rapidly approaching a point where finding the variants won’t be much of a problem.

Instead, we are facing two significant challenges. First, identifying the subset of variants have functional significance – separating the wheat from the chaff, if you will. Second, understanding how these functional variants contribute to a phenotype. This is soon to be the frontier in genetics and genomics. It merits, I think, a discussion of some of the strategies that have been used to go beyond variant detection, to isolate disease-causing variants and assess their functional impact.

Strategy 1: Process of Elimination

This approach (to my knowledge) is best demonstrated in whole-genome, exome, or pooled sequencing of samples from individuals with rare inherited diseases. It’s essentially a filtering strategy where you start with a list of candidate variants and whittle it down using several criteria:

- Pedigree information, especially variants that do not segregate with the disease in Mendelian disorders.

- Control variants, usually identified in HapMap samples or other individuals not affected by the disease.

- Gene structure information, which serves to eliminate synonymous or non-coding variants.

- Evolutionary conservation, to prioritize variants in sequences that are conserved across species.

This strategy has worked well for a handful of rare, inherited diseases like Miller syndrome and severe hypercholesterolemia. There are, however, so many things that can go wrong. The pedigree or assumed mode of inheritance could be wrong. The causal variant might be synonymous or even noncoding (e.g. in a transcription factor binding site). The conservation trick in particular worries me. True, many of the known disease-causing mutations map to conserved amino acid residues, but certainly not all of them.

Strategy 2: Recurrence

This is a developing strategy to identify key mutations and pathway alterations in cancer genomes. Because tumors are genetically unique, and often possess thousands of acquired (somatic) mutations, pedigree analysis and control samples are less informative. Instead, we reason that passenger mutations should occur randomly, mutations key to tumor development and progression are likely to be recurrent (i.e. found in other tumors of the same type). By this reasoning, the more important a mutation, the higher its rate of recurrence. TP53 mutations are a good example of this; in ovarian cancer, more than 80% of tumors carry a TP53 mutation. This is why databases like Sanger’s Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC) are such powerful tools. As these catalogues grow, having an available panel of additional tumors to screen for novel mutations may become less critical.

Strategy 3: Computational Evaluation

A growing suite of tools and annotation databases enable computational assessments of putative variants to predict their effect in vivo. SIFT and Polyphen are well-known examples of these. The UCSC Genome Browser Database contains dozens of genome-wide annotation datasets (both computational and experimental); many of these are presumed-regulatory regions that form the basis for our “Tier 2” classification (non-coding conserved/regulatory variants). There are also motif-scoring algorithms that evaluate a mutation’s effect on the binding affinity of trancription or splicing factors. These types of inferences are both interesting and helpful, when assessing a mutation’s functional effect. They’re not convincing, however, without supporting experimental evidence.

Strategy 4: Molecular Validation

This may be the most difficult strategy, but potentially the most informative one. A myriad of experimental techniques can be applied to assess a mutation’s functional effect in vivo or in vitro. For coding mutations, the first thing we typically assess is mRNA expression (by RT-PCR or RNA-Seq), to determine (1) if the affected gene is expressed in the tissue of interest (e.g. the retina for studies of retinitis pigmentosa) and (2) whether the mutant allele affects it. Many known disease-causing mutations ablate expression of the mature mRNA, because they introduce splicing defects, mRNA instability, or other effects. A number of other molecular biology tools can also be applied:

- Western blot, to determine protein expression

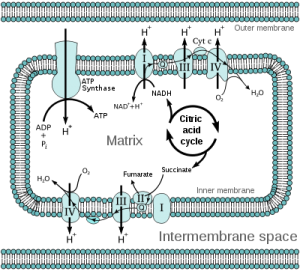

- Enzyme activity assays, such as the complex I rescue technique that has been applied to characterize mutations in patients with complex I deficiency (see my last post).

- Recombinant DNA techniques, such as a luciferase assay to assess mutations in gene promoters

- Colony growth assays, especially for somatic mutations, to determine if mutations confer a growth advantage or invasion potential.

Specialized Sequencing Techniques

A number of recently-developed applications of massively parallel sequencing can be used to assess the functional impact of candidate mutations. RNA-Seq can detect allele-specific expression and alternative splicing. ChIP-Seq can assess protein-DNA interactions and theoretically detect allele-specific DNA binding. Methyl-Seq can be used to profile DNA methylation, either at specific loci or (for methylation pathway mutations) genome-wide. MiRNA-Seq and HITS-CLIP, techniques that measure microRNA expression or isolate miRNA-transcript interactions, also have potential for characterizing mutation effects. Many of these high-throughput techniques stand poised to supplant their traditional experimental counterparts.

Given the wide array of experimental tools, it’s disappointing when reports of new (possible) disease-causing mutations lack sufficient functional validation. I find myself unconvinced when the answer is supported by “it segregates with the disease” or worse, “we filtered everything else.” So when I read new papers that claim to have identified disease-causing variants, my answer is this: Great mutation. Is it functional?