Metagenomic profiling, also called metagenomic shotgun sequencing (MSS) represents a powerful application made possible by the digital nature of next-gen sequencing technologies. In it, one basically sequences a sample isolate obtained from somewhere — a shovelful of dirt, a scoop of plankton, or anything else that contains living organisms. MSS has proven particularly useful to studies of the human microbiome, or in layman’s terms, all of the bacteria/viruses/fungi that live in our bodies.

Many such microbiota are beneficial or simply commensal (not doing harm) with us. Others, like methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), can cause severe disease. Most efforts to chart the human microbiome have focused on bacteria, whose relatively stable genomes make them amenable to assay development. Viruses, in contrast, are somewhat under-studied. Part of that is due to the small size and highly variable nature of viral genomes.

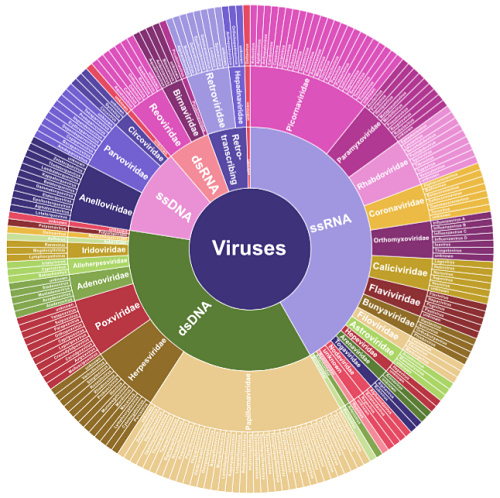

A new study in Genome Research showcases a capture-based enrichment strategy to improve virome sequencing. The ViroCap panel was developed by Todd and Kristine Wylie, who happen to be colleagues of mine at the McDonnell Genome Institute. The panel enriches for nucleic acids from 34 families of DNA or RNA viruses that infect vertebrate hosts, beautifully illustrated in Figure 1 from the paper:

At the time of the ViroCap design, NCBI GenBank contained the sequenced genomes of around 440 viral species, for a total of about 1 Gbp (billion base pairs) of sequence. Yet the maximum size of a capture reagent (for Nimblegen SeqCap EZ) was 200 million bp. So the authors winnowed down the list by removing:

- Bacteriophages (only infect bacteria)

- Human endogenous retroviruses (already in our constitutional genome)

- Viruses that infect only fungi, archaea, algae, or invertebrate hosts

The resulting targets represent 34 viral families, comprising 190 annotated genera and 337 different species. After considerable bioinformatics efforts, the authors produced a ~200 Mbp sequence target and worked with Nimblegen to have it designed.

ViroCap Evaluation in Clinical and Research Samples

To validate the new reagent, the authors leveraged two small cohorts of patient samples that had tested positive for viral infection by molecular and/or PCR-based detection assays. Illumina sequencing libraries were created for each of the sixteen (total) samples, and then sequenced in parallel with and without the ViroCap enrichment. The results are pretty striking:

| Performance Metric | Clinical Samples (n=8) | Research Samples (n=8) |

| Viruses detected (MSS): | 10 | 14 |

| Viruses detected (ViroCap): | 11 | 18 |

| Median coverage breadth (WSS): | 2.1% | 2.0% |

| Median coverage breadth (ViroCap): | 83.2% | 75.6% |

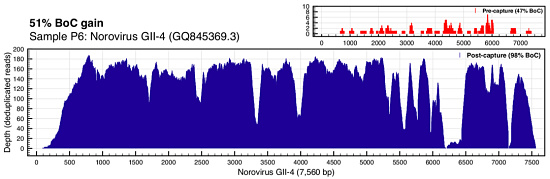

ViroCap enables better detection and improved overall breadth of coverage for viral genomes. Figure 1 illustrated this very well. Here’s the coverage of norovirus (often the fact of cruise ship outbreaks) in sample P6:

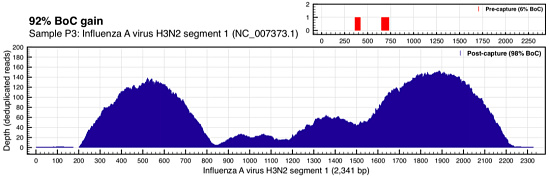

You’re looking at the depth of coverage achieved across the reference by metagenomic shotgun sequencing (top right, in red) compared to the coverage of ViroCap sequencing. The breadth of coverage was 51% higher with ViroCap, and the average depth went from about 3x to 180x by my estimate. Here’s Influenza A (H3N2):

In this case, the virus went from essentially undetected (2 reads) in WSS to 20x-140x average depth with ViroCap.

Variable Virus Genomes

One potential criticism of capture-based assays for viral sequencing is that highly variable genomes might not be well-captured due to substantial divergence from the reference sequence used to design probes. We know that 100% sequence identity isn’t required, or else capture sequencing methods (e.g. exome sequencing) would never have become a mainstay for human genetics. Yet viral genomes are both variable and highly mutable, so it’s important to know how well ViroCap addresses that.

To investigate this, the authors looked at samples positive for anelloviruses, a highly divergent group of single-standed DNA viruses that have a common core genome but up to 50% nucleotide sequence diversity. In those samples, contigs with sequence identity as low as 62% were completely covered with ViroCap sequencing. The most divergent contig observed had 58% identity and was missing about 13% of the target region, suggesting that viral genomes diverging ~40% or more from the reference will begin to lose coverage with ViroCap.

In summary, Wylie et al have developed a valuable resource for viral metagenomic sequencing that should have immediate utility in both research and clinical settings.

References

Wylie TN, Wylie KM, Herter BN, & Storch GA (2015). Enhanced virome sequencing through solution-based capture enrichment. Genome research PMID: 26395152