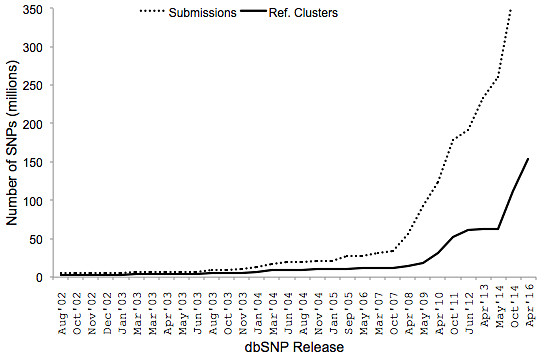

Earlier this week, I took a look at the dbSNP VCF file for build 147 (human) with Ben Kelly from the White Lab at NCH. Even summary statistics took a while to generate, and soon we realized why: dbSNP now contains a jaw-dropping 152.7 million reference variants. Roughly speaking, that’s one variant for every 20.5 base pairs in the human genome. They’re not all rare variants, either: 86 million variants are classified as common (G5, G5A, or COMMON), with minor allele frequencies >1% in at least one population.

dbSNP’s Ridiculous Growth

During the HapMap project in 2003-2004, we were astonished to see dbSNP hit 10 million variants. My boss at the time, Ray Miller, told me that some thought it could one day hit 50 million. We thought it might take decades, but dbSNP surpassed 50 million refSNPs just seven years later.

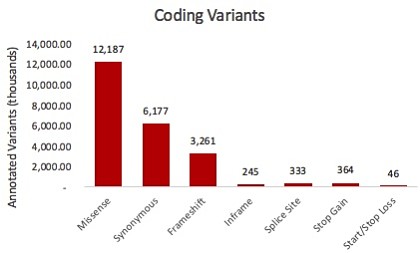

Even more astonishing are the 6+ million coding variants: depending on how you define the exome, that’s about one variant every 5 or 6 base pairs in coding regions. Compounded by the fact that a single variant might affect multiple transcripts/genes, the number of observed human coding variants exceeds 22 million.

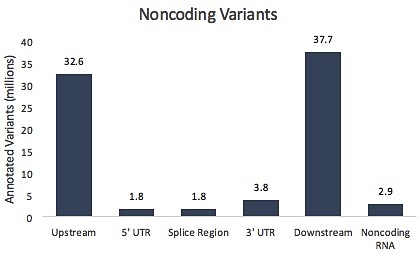

That being said, the fact remains that the vast majority of known variants in our genome lie outside of protein-coding exons. When annotated with snpEff, there are more than 80 million variants within or nearby genes, where they might play a regulatory role (again, multiple transcripts = multiple annotations per variant).

The Evolving Utility of dbSNP

In the early days of next-generation sequencing, dbSNP provided a vital discriminatory tool. In exome sequencing studies of Mendelian disorders, any variant already present in dbSNP was usually common, and therefore unlikely to cause rare genetic diseases. Some of the first high-profile disease gene studies therefore used dbSNP as a filter. Similarly, in cancer genomics, a candidate somatic mutation observed at the position of a known polymorphism typically indicated a germline variant that was under-called in the normal sample. Again, dbSNP provided an important filter.

Now, the presence or absence of a variant in dbSNP carries very little meaning. The database includes over 100,000 variants from disease mutation databases such as OMIM or HGMD. It also contains some appreciable number of somatic mutations that were submitted there before databases like COSMIC became available. And, like any biological database, dbSNP undoubtedly includes false positives.

On the bright side, however, the rapid generation of genomic data worldwide has enabled deeper characterization of the variants that we know about. The 1,000 Genomes Project contributed genome-wide data for 2,504 individuals from several continental groups, while the Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC) has compiled gene-centric data from 60,706 individuals at the time of writing.

The Value of Variant Allele Frequencies

As a central repository for variant allele frequency (VAF) data, dbSNP can be a powerful resource for human genetics studies. Of particular relevance for rare disease genetics are the variant allele frequencies (VAFs) in worldwide populations. For a rare autosomal recessive disorder affecting 1 in 100,000 individuals, compound-heterozygous variants with VAFs of 0.01 in a certain population are too common: their combined frequency is 0.0001, or 1 in 10,000. In contrast, most known disease-causing variants — mutations that have been imported from OMIM, for example — are exceedingly rare.

Thus, while the mere presence of a variant in dbSNP is a blunt tool for variant filtering, dbSNP’s deep allele frequency data make it incredibly powerful for genetics studies: it can rule out variants that are too prevalent to be disease-causing, and prioritize ones that are rarely observed in human populations. This discriminatory power will only increase as ambitious large-scale sequencing projects like CCDG make their data publicly available.

Ancestry and Inclusion

Importantly, allele frequency data are most useful when the population matches the ancestry of the sample(s) being studied. In their current form, our databases are skewed towards major population groups (northwest European, East African, and East Asian). Many important geographic and ethnic groups are still under-represented. The reasons for this are complex, and not the focus of this post, but I think we can all agree that it’s vital to seek out and include samples from diverse ancestries as large-scale sequencing efforts move forward.

In Summary

At 150+ million variants, dbSNP is a massive beast, and still offers a useful discriminatory tool when used correctly. Proceed with caution.

dbSNP is a very good resource because it centralizes annotation on SNPs from all the sources and provides an ID for each. However, personally I have always been wary of using it for any analysis. I may be wrong, but I think there are too many false positives and non reproducible data. I prefer to use curated data such as EBI EVA or Uniprot variants, which passed through an additional curation process.

The variant density ( count per Mb ) seems higher in exome than non-coding part. Probably a selection biais. More Exome has been sequenced than Whole genome. No ?

You’re absolutely right: it’s an ascertainment bias. A lot more exomes have been sequenced than whole genomes.