It’s no secret that while genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have implicated thousands of genetic loci in human phenotypes, the variants uncovered collectively explain only a fraction of the observed variance between individuals. The reasons for this “missing heritability” are a subject of vigorous debate in the scientific community. One possible explanation is that rare (low-frequency) variants — which are poorly represented on the arrays used for GWAS — underlie a substantial proportion of the variability.

This idea is intuitive: in theory, large-effect variants would be kept at low frequency by natural selection, a pattern that’s well established for mutations that cause rare single-gene disorders. It also makes a strong argument for large-scale sequencing for common complex disease, which is the purpose of the NHGRI’s flagship CCDG program. The problem, of course, is that we can’t really understand the contribution of low-frequency variants to human disease without actually performing such an experiment.

A new study in this week’s issue of Nature represents one of the first and highest-profile attempts to do so for a common disease. Type II diabetes (T2D) affects 29 million people in the United States (according to the CDC), which is about 9.3% of the entire population. It also has a strong genetic component, and has thus been a priority GWAS target for over a decade. So far, GWAS efforts have reported 80 robust associations, largely involving common (MAF>5%) variants that have very small effects on disease risk.

In the current study, Christian Fuchsberger and his 300+ co-authors used a combination of genome sequencing, exome sequencing, genotyping, and imputation to examine the genetic architecture of type II diabetes. This report is the fruit of a years-long collaboration between two consortium efforts: GoT2D, which applied whole-genome sequencing to individuals of European ancestry, and T2D-GENES, which performed exome sequencing in multi-ethnic cohorts. Here’s a summary of the data generated:

| Genome-wide Data (European ancestry) | Cases | Controls | |

| Low-coverage (5x) whole genome sequencing: | 1,326 | 1,331 | |

| Genotype imputation in 13 other cohorts: | 11,645 | 32,769 | |

| Total: | 12,971 | 34,100 | |

| Exome-centric Data (5 ancestry groups) | Cases | Controls | |

| Deep (82x) exome sequencing: | 6,504 | 6,436 | |

| SNP array genotyping (2.5 million sites): | 28,305 | 51,549 | |

| Total: | 34,809 | 57,985 |

Genome Sequencing Coverage Matters

I think it’s important to point out the nuance of whole-genome sequencing coverage. Generally, we target 30x coverage for a whole-genome of a germline (i.e. non-tumor) sample, which provides excellent power for variant detection. Some groups have touted 20x as a possible minimum threshold, and I’m comfortable with that.

But low-coverage (5x) whole genome sequencing is a whole different animal. WGS coverage is like a bell curve: while many positions will have 5x coverage, some will have 1-3x and some will have 7-10x. Even for this group of authors, which include some of the top experts on NGS variant calling, this presents a significant challenge for variant detection.

Simply put, at 5x coverage, a number of rare and/or hard-to-call variants (e.g. SVs) will be missed.

Useful WGS Metrics

In spite of my concerns, I’m a sucker for summary metrics in large-scale WGS datasets. Here are some highlights from low-coverage WGS of 2,657 European-ancestry individuals:

- 26.7 million variants were detected, genotyped, and phased, including 1.5 million small indels and 8,876 large (>100 bp) deletions.

- Individuals harbored an average of 3.30 million genetic variants, including 271,245 indels and 669 deletions.

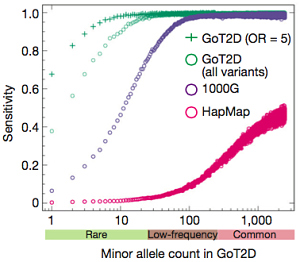

- 420,473 common SNVs and 2.4 million low-frequency SNVs were poorly tagged by genotype arrays (r-squared < 0.30), and thus haven’t been interrogated by any T2D GWAS to date.

Genome-wide Single-variant Associations

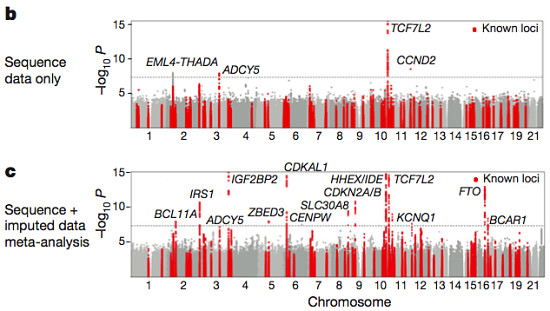

The primary association analysis uncovered 126 variants at 4 loci that were associated with T2D, three of which were known. EML4 was novel, but when the authors imputed sequencing variants into a much larger sample collection (44,414 individuals from 17 other studies), the association didn’t hold up. Another novel signal (CENPW) did appear, and this was replicated in an independent cohort.

Fuchsberger et al, Nature 2016

In summary, the meta-analysis of sequencing and imputed data examined 26.7 million variants in over 47,000 individuals of European ancestry. That’s a massive association study with extremely high resolution, yet it recapitulated only 13/80 loci (16%) known to be “robustly associated” with T2D, and uncovered only one new locus. I find that a bit discouraging, and I’m sure the authors did, too.

Coding Variation in Type II Diabetes

The analysis of exome data fared little better, I’m afraid. The authors combined exome sequencing data from 10,437 individuals representing five ancestry groups (European, South Asian, East Asian, Hispanic, and African American) with equivalent data from the WGS study for a joint dataset comprising 12,940 individuals. They identified:

- 3.04 million variants overall, of which 1.19 million were protein-altering

- ~9,243 synonymous, 7,636 missense, and 250 protein-truncating variants per individual

Single-variant testing yielded only a single significant result, (PAX4 p.Arg192His, a.k.a. rs2233580) that was only observed in East Asian individuals. Gene-level aggregation testing yielded no exome-side significant finding. Limiting the analysis to 634 genes in known associated loci uncovered an association (FES in South Asians, driven by a single likely-causal variant) that met the more forgiving threshold for significance.

To increase power, the authors integrated SNP genotypes from 2.5 million sites in about 79,000 additional cases and controls (all European ancestry) obtained using a custom Illumina SNP chip. Integrating these with the exome data yielded an exome-centric dataset of more than 90,000 individuals. Some 18 variants at 13 loci exceeded genome-wide significance, but all were common (MAF>5%), and only one (MTMR3) was outside of known GWAS loci.

No Evidence for Synthetic Association

Back in 2010, Goldstein and colleagues proposed the concept of “synthetic association” — the idea that common GWAS signals may be due to individually rare causal variants which cluster on certain common haplotypes. The thinking was that sequencing in GWAS regions might therefore reveal all of these causal variants. This would offer an intriguing explanation for the fact that most lead GWAS hits lie outside of coding regions. It might be possible that nearby rare causal variants were in LD with the tag SNP, and these (not the tag SNP) exerted the causal effect on disease risk.

The authors tested this hypothesis in T2d using the WGS dataset for 2,657 individuals, which they describe as having “near-complete ascertainment of genetic variation.” They took the 10 T2D GWAS loci with the strongest support in their study, and looked for low-frequency missense variants within 2.5 million base pairs of the common index SNV. None of the loci showed supporting evidence of “synthetic association,” and 8/10 were convincingly not consistent with the proposed phenomenon.

Thus, while synthetic association might well underline common GWAS signals for other phenotypes, it does not appear to do so for T2D.

The Contribution of Rare and Common Variants

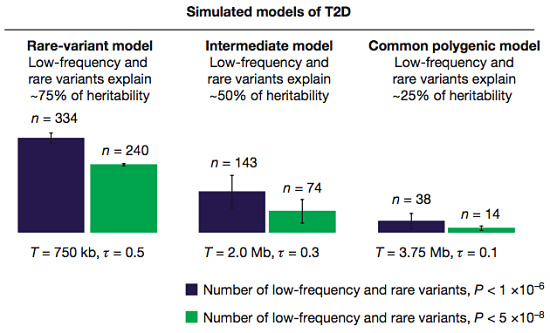

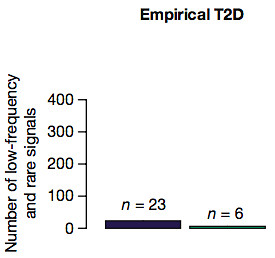

To model the disease architecture of T2D, the authors conducted an elegant experiment. They simulated three possible models which had seemed plausible prior to large-scale sequencing, and computed the number of associated low-frequency and rare variants that would be uncovered with their study design.

In the first two models, low-frequency variants explain a significant proportion of the heritability, and over a hundred of them should have been uncovered at the more forgiving significance threshold. In a third model, where rare variants make a minority contribution, they’d uncover only a few dozen.

Next, the authors compared these outcomes to their actual results. Only 23 low-frequency and rare variants achieved significance, which is nowhere close to the first two models (the ones that suggest a major role). It’s most similar to the common polygenic model of disease for T2D, suggesting that this study supports a minor role for rare and low-frequency variants.

In Summary

Overall, I found this to be a comprehensive and extremely well-written paper of the caliber we’d expect to see in Nature. It represents years of work by more than 300 contributing authors, and probably the first study of many to come. While the number of new discoveries may be a tad disappointing, the authors have uncovered novel loci and secondary signals. They’ve also done a great deal to shed light on the genetic architecture of this common complex disease, particularly as far as coding variants are concerned.

We will need, and I hope to see, many efforts like this to understand the genetic architecture of other diseases and important human traits.

References

Fuchsberger C, Flannick J, Teslovich TM, Mahajan A, Agarwala V, Gaulton KJ, Ma C, Fontanillas P, Moutsianas L, McCarthy DJ, Rivas MA, Perry JR, Sim X, Blackwell TW, Robertson NR, Rayner NW, Cingolani P, Locke AE, Tajes JF, Highland HM, Dupuis J, Chines PS, Lindgren CM, Hartl C, Jackson AU, Chen H, Huyghe JR, van de Bunt M, Pearson RD, Kumar A, Müller-Nurasyid M, Grarup N, Stringham HM, Gamazon ER, Lee J, Chen Y, Scott RA, Below JE, Chen P, Huang J, Go MJ, Stitzel ML, Pasko D, Parker SC, Varga TV, Green T, Beer NL, Day-Williams AG, Ferreira T, Fingerlin T, Horikoshi M, Hu C, Huh I, Ikram MK, Kim BJ, Kim Y, Kim YJ, Kwon MS, Lee J, Lee S, Lin KH, Maxwell TJ, Nagai Y, Wang X, Welch RP, Yoon J, Zhang W, Barzilai N, Voight BF, Han BG, Jenkinson CP, Kuulasmaa T, Kuusisto J, Manning A, Ng MC, Palmer ND, Balkau B, Stančáková A, Abboud HE, Boeing H, Giedraitis V, Prabhakaran D, Gottesman O, Scott J, Carey J, Kwan P, Grant G, Smith JD, Neale BM, Purcell S, Butterworth AS, Howson JM, Lee HM, Lu Y, Kwak SH, Zhao W, Danesh J, Lam VK, Park KS, Saleheen D, So WY, Tam CH, Afzal U, Aguilar D, Arya R, Aung T, Chan E, Navarro C, Cheng CY, Palli D, Correa A, Curran JE, Rybin D, Farook VS, Fowler SP, Freedman BI, Griswold M, Hale DE, Hicks PJ, Khor CC, Kumar S, Lehne B, Thuillier D, Lim WY, Liu J, van der Schouw YT, Loh M, Musani SK, Puppala S, Scott WR, Yengo L, Tan ST, Taylor HA Jr, Thameem F, Wilson G, Wong TY, Njølstad PR, Levy JC, Mangino M, Bonnycastle LL, Schwarzmayr T, Fadista J, Surdulescu GL, Herder C, Groves CJ, Wieland T, Bork-Jensen J, Brandslund I, Christensen C, Koistinen HA, Doney AS, Kinnunen L, Esko T, Farmer AJ, Hakaste L, Hodgkiss D, Kravic J, Lyssenko V, Hollensted M, Jørgensen ME, Jørgensen T, Ladenvall C, Justesen JM, Käräjämäki A, Kriebel J, Rathmann W, Lannfelt L, Lauritzen T, Narisu N, Linneberg A, Melander O, Milani L, Neville M, Orho-Melander M, Qi L, Qi Q, Roden M, Rolandsson O, Swift A, Rosengren AH, Stirrups K, Wood AR, Mihailov E, Blancher C, Carneiro MO, Maguire J, Poplin R, Shakir K, Fennell T, DePristo M, Hrabé de Angelis M, Deloukas P, Gjesing AP, Jun G, Nilsson P, Murphy J, Onofrio R, Thorand B, Hansen T, Meisinger C, Hu FB, Isomaa B, Karpe F, Liang L, Peters A, Huth C, O’Rahilly SP, Palmer CN, Pedersen O, Rauramaa R, Tuomilehto J, Salomaa V, Watanabe RM, Syvänen AC, Bergman RN, Bharadwaj D, Bottinger EP, Cho YS, Chandak GR, Chan JC, Chia KS, Daly MJ, Ebrahim SB, Langenberg C, Elliott P, Jablonski KA, Lehman DM, Jia W, Ma RC, Pollin TI, Sandhu M, Tandon N, Froguel P, Barroso I, Teo YY, Zeggini E, Loos RJ, Small KS, Ried JS, DeFronzo RA, Grallert H, Glaser B, Metspalu A, Wareham NJ, Walker M, Banks E, Gieger C, Ingelsson E, Im HK, Illig T, Franks PW, Buck G, Trakalo J, Buck D, Prokopenko I, Mägi R, Lind L, Farjoun Y, Owen KR, Gloyn AL, Strauch K, Tuomi T, Kooner JS, Lee JY, Park T, Donnelly P, Morris AD, Hattersley AT, Bowden DW, Collins FS, Atzmon G, Chambers JC, Spector TD, Laakso M, Strom TM, Bell GI, Blangero J, Duggirala R, Tai ES, McVean G, Hanis CL, Wilson JG, Seielstad M, Frayling TM, Meigs JB, Cox NJ, Sladek R, Lander ES, Gabriel S, Burtt NP, Mohlke KL, Meitinger T, Groop L, Abecasis G, Florez JC, Scott LJ, Morris AP, Kang HM, Boehnke M, Altshuler D, & McCarthy MI (2016). The genetic architecture of type 2 diabetes. Nature PMID: 27398621